Why this young theologian was drawn to Reformed evangelicalism

Editors’ note: “This is the first article of a series The Messenger is commissioning on “the appeal of _____.”

Our request to writers was that they explain what it is they find appealing about other, not quite EMC, variations of Christian thought and practice. There’s nothing heretical here—rather these are convictions and worship practices we encounter as we visit other churches, listen to Christian programming or read Christian literature—and most of the time we barely notice, because, as Paul says, Christ is being preached, and these are our brothers and sisters.

Just as Rick Langer encouraged at the SBC leadership conference this past March, we need to understand what drives our differences. There is more behind our convictions than we can explain intellectually.

Our hope is that the series gives us insight into each other and leads to great conversations.”

At one point the title to Collin Hansen’s 2008 book Young, Restless, Reformed would have described me quite well. I was young (in my early 20s), restless (in many ways) and Reformed (drinking regularly from the well of the three Johns: Piper, Edwards and Calvin).

(iStock)

As an eager college student, I bought John Calvin’s twenty-two volume commentary set on the entire Bible (the 500th year anniversary edition of course). I laboured with much difficulty through Johnathan Edward’s philosophical works, such as “The End for Which God Created the World,” because I believed it would somehow be for my good. I visited Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis with hopes of hearing God glorified firsthand through the preaching of John Piper. And I planned to go to a flagship Calvinist seminary in the U.S. to sharpen these convictions.

I understand the appeal of Reformed evangelicalism not because it was the Christian tradition I grew up in (i.e., Anabaptism), and not because I felt pressured to do so (though a friend’s interest in the movement was also a pull factor). I did so because it genuinely appealed to me as a young adult in search of his theological moorings and because I wanted to think correctly about God. In this article, I intend to speak about the appeal of Reformed evangelicalism from this experience.

A word about terms. They can be tricky. In one sense, all Protestants are “reformed” because we are all descendants of the Reformation. But that is not how the term is typically used. At the risk of oversimplification, I will use the term in reference to the major branch within Protestantism known as Calvinism that began in the 16th century under the reformer John Calvin, and continues to find expression today in various church groups, perhaps most notably the New Calvinist movement which rose to prominence in the early 21st century and is the focus of Hanson’s book.

It goes without saying that I do not pretend to speak for even most people who are drawn to the Reformed expression of evangelicalism, although I expect some to find they can relate. But from my experience there were four factors that had a strong appeal to me in my theological journey.

A rich pedigree

The first is its rich pedigree. There can be no doubt about it, Reformed evangelicalism boasts of a pedigree rivalled only by the Catholic Church (primarily, because 75 percent of church history belongs to it). While we can quarrel over who exactly belongs where, no one else claims to be the theological descendants of Martin Luther and John Calvin, Richard Baxter and John Bunyan, George Whitfield and Jonathan Edwards, Charles Spurgeon and Charles Hodge, Herman Bavinck and Abraham Kuyper, Karl Barth and Martyn Lloyd-Jones, J. I. Packer and Timothy Keller, never mind the many (and often popular) pastors and professors today who identify as either upper- (“R”) or lower-case (“r”) “Reformed” in their congregations and classrooms.

To use a term from the world of sports, this team is “stacked” with Protestant superstars. Reformed evangelicalism is the Team Canada of international hockey, trying to juggle around the likes of Sidney Crosby, Connor McDavid and Nathan MacKinnon. Who does not want to play for them, when it feels like almost every major theologian, missionary and pastor within the Protestant tradition is claimed as their “guy”? Pair this together with the tradition’s emphasis on God’s election of individuals for salvation (Ephesians 1:4), and you have (at its best) a strong sense of assurance that you are on the winning team, or (at its worst) an unmatched quality of arrogance about you that comes from believing you must be something special for having made this team.

Now, it is always dangerous to guess at someone else’s motives, which is why I don’t pretend to speak for anyone but myself. But whether one is driven by the simple desire to fit in, to be on the winning team, peer pressure to be on the right side of church history, theological FOMO, or the sense that the majority must be right when it comes to this question, one cannot deny that Reformed evangelicalism’s pedigree and aura of being the “winning team” is a drawing factor.

A robust theological system

Connected to that, is the reality that the Reformed tradition offers a robust and comprehensive theological system through which to view, well, everything. Regardless of if one always finds their answers satisfactory, they have not left many theological stones left unturned. And what else would you expect with the roster of Protestant intellectual superstars mentioned above?

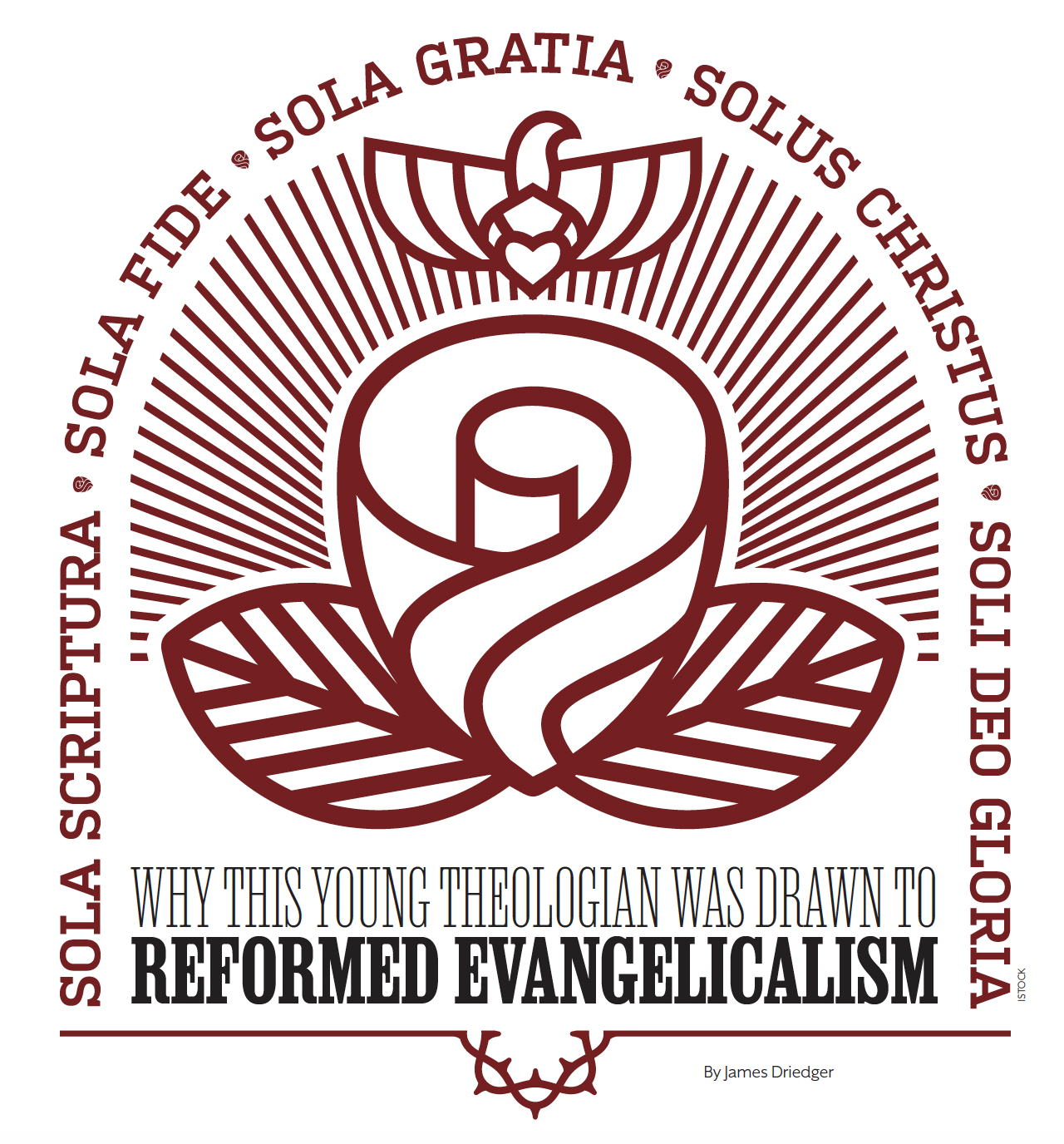

(iStock)

The Reformed tradition contains a rich reservoir of Christian thought that not only includes the Institutes and Church Dogmatics, but also the Belgic and Westminster Confessions of Faith, works like The Pilgrim’s Progress and The Book of Common Prayer that continue to shape the modern West’s language and imagination, and the present day output of reformed schools (Southern Baptist Theological Seminary), publishers (Crossway) and organizations (The Gospel Coalition) to name just a few. When it comes to leaving behind a depository of biblical and theological reflection, no other Protestant tradition can hold a candle to the quantity of material produced by the Reformed tradition—not least those who had to run for their lives for a few centuries before settling down.

Which is why as a young adult with minimal understanding of the state of theological discussion and development in the broader church, and the understanding I did have coming mainly from the charismatic organization I was a part of at the time, when I was introduced to the Reformed tradition, I felt like I was being offered a feast of the finest foods. As much as I love the charismatic church—and they truly are a gift to the body of Christ—I found it theologically lean in comparison to what Reformed theology had to offer. Not only did the Reformed tradition offer what felt like an endless buffet of biblical-theological answers to every question I could possibly imagine, but their answers carried a sense of objectivity in comparison to the subjective revelatory gifts I was accustomed to.

A clear Scripture

Reformed evangelicalism’s comprehensive theological system could not exist apart from their belief that the Bible can be easily read and understood. The Protestant principle of sola scriptura, which gives the Bible a privileged place of authority in all matters of life and faith, coupled with a belief in the perspicuity of Scripture (i.e., its clarity), has given the Reformed tradition a lot of confidence in reading and applying the Bible in every aspect of life.

Without denying the difficulties common to interpretation, Reformed evangelicalism believes, functionally, that the Bible says what it means and means what it says. From my experience, this means that their reading and application of Scripture tends to be more black-and-white, leaving less under the heading of mystery than what other traditions are comfortable with.

As such, they can almost never be faulted for playing loose with Scripture or treating it lightly. Compared to some of their more progressive evangelical peers, Reformed evangelicalism takes the Bible, and their interpretation of it (and often themselves as well) very seriously. In fact, at times one can get the sense that they think they are the only ones who do.

One result of this is that they have a Bible passage and theological answer for everything. This includes (but is by no means limited to) a concise theodicy for suffering and evil (via God’s providence), the correct sequence of events by which everyone is saved (the ordo salutis), clear gender roles within the church and home (often complementarian), a confident explanation for how exactly the atonement of Christ works (often penal substitution), and the consummate model by which to structure your church’s organizational leadership (either an elder board or presbytery).

And this is attractive in a chaotic world. The Western world feels for many like it is being tossed to and fro by the ever-changing mood swings of our culture. It also lacks the clarity or the nerve to call anything right or true. Which explains why many are increasingly drawn toward people and ideas that are clear-cut and confident. We want an anchor to hold onto amidst this storm. And it is in this climate, that the Reformed theological tradition projects a confidence in God and his clearly revealed will for our lives in Scripture, that is appealing to many.

A big God

I think it goes without saying that all of this is possible in the Reformed tradition because of who God is. There are many words one could use—transcendent, omnipotent, or sovereign—but the God of Reformed evangelicalism is a big God who is intimately involved in even the smallest details of our lives. His sovereign rule lays claim to every square inch of creation, and he is at work bringing about his will and purposes from every dice that is rolled in Las Vegas (Proverbs 16:33), to determining who will survive a tsunami in the Indian Ocean (Amos 3:6), and ultimately who will be a vessel of honourable or dishonourable use in his hands (Romans 9:22).

And this is a view of God that many are drawn to. A God who cannot be surprised by anything is a God who is in control, which is comforting. Who wants a God that is not in control? A God who knows the end from the beginning is a God whose plans cannot be thwarted by any other agent, which offers us security. A God who could be affected by other agents is too unpredictable to entrust our salvation in. And living in a universe where God is directly involved in the workings of his creation means that nothing in the end will be said to have been random or wasted, because it will be seen as having been part of God’s perfect plan all along. Who wants to worship a God, after all, who is unable to work all things together for our good and for his glory?

Reformed evangelicalism could be criticized for thinking their theological system gives God the most glory, and that it must be the only right way to think about God because of it; but it cannot be faulted for placing God at the centre of its theological system and making much of him. God is, after all, the subject of Christian faith. And Reformed evangelicalism intends to do everything within its power to direct us toward God who is worthy of our worship. And as creatures hardwired to worship something, that is appealing.

Conclusion

Not everyone finds Reformed evangelicalism or every aspect of it as appealing as the next. But it is not hard to understand why it appeals to many: It makes much of God. It celebrates that God has revealed himself to us clearly in Scripture, which instills confidence that we can understand his will for our lives. And then it provides us with a great cloud of Protestant intellectual witnesses to spur us on in the faith. And that is what I found appealing about Reformed evangelicalism.

Now that was over a decade ago. And since then, I have continued to read Scripture, study theology, and think about God to the best of my ability with the broader church. And I have come to learn that one can have a big God, a clear Scripture, a robust theological system, and still lean on all the great theologians of the past, without holding to many of the Reformed theological distinctives.

And as you may have guessed, I am not as aligned with Reformed evangelicalism as I was even a decade ago. And it is one of the Reformation’s own principles—reformata et semper (“reformed and always reforming”)—that gave me the permission I needed to keep expanding my theological vision when I came up against the shortfalls and pitfalls of Reformed evangelicalism. No human theological system is ever complete or immune from Scripture’s scalpel, not least Reformed theology. And while it is not as catchy, these days I prefer the description: still young, less restless, and always reforming.