Missional, faithful, and with a deep love of Scripture

the appeal of fundamentalism

Editors’ note: This is the fifth in a series of six articles exploring some of the theological variation we find in the EMC. Our goal is to grow in our understanding of why certain theological positions are attractive to people in our churches, with the hope that this will help us have more informed conversations.

The next and final article will be on the appeal of the EMC’s particular blend of evangelicalism and Anabaptism.

There are certain words that conjure up vivid images in our minds. For instance, if I were to say “heroic,” I am sure that you have specific thoughts come to mind. For some it may be a firefighter pulling people from a burning building with little regard for their own lives. Others may think of Christian martyrs, both past and present, who have willingly endured persecution and death rather than deny Christ. For myself, I tend to gravitate toward the heroic imagery of D-Day soldiers storming the beaches of Normandy in 1944, advancing in the face of ferocious resistance. Perhaps I myself am heroic for admitting such a thing to the broader pacifist wing of the EMC!

In the same respect, the term “fundamentalist Christian” can produce vivid images in our minds. For many individuals today, it may dredge up deep feelings and emotional reactions. Images of angry-looking folk protesting military funerals, of street preachers condemning the broader public to hell, or of narcissistic, legalistic, and abusive cult-like church leaders are common. Some equate fundamentalists with ignorance , which is sadly a reputation that too many have rightfully earned. Indeed, when those in media use the title, it is often in the attempt to paint the individuals in question as being extremists or radicals, or some other group that ought to be rejected outright.

Due to this negative stigma, many Christians distance themselves from the title “fundamentalist,” and I cannot blame them given the current cultural perception. I personally know numerous individuals who have been completely turned off Christianity because of the teachings of some of these fundamentalist individuals or organizations, and many more who have distanced themselves from the conservative side of the Christian spectrum. That is something that fills me with both sorrow and anger. I understand it personally as well; there have been times in my own life where I had profoundly negative experiences with strict fundamentalist individuals, and my emotional reaction was to cease to have any meaningful association with them.

Yet are we right to so readily abandon this designation? While I may have distanced myself from adopting this title given the modern-day interpretation and definition, I am also wary of throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. (This should not be a surprise given that I am writing an article defending the validity and appeal of fundamentalism!) However, to understand where I am coming from, I think it is worthwhile to go back in history.

A brief history lesson

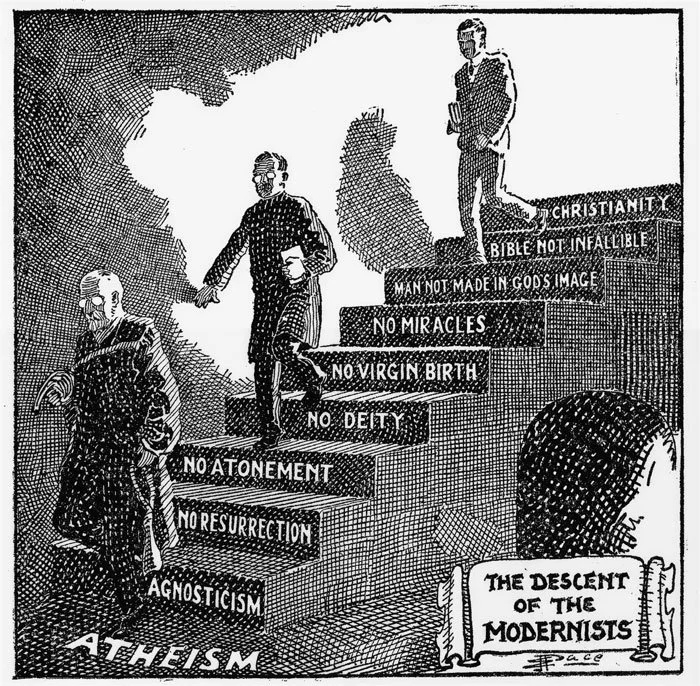

“The Descent of the Modernists” by Ernest James Pace, a fundamentalist cartoon portraying modernism as the descent from Christianity to atheism, was first published in Seven Questions in Dispute by William Jennings Bryan in 1924. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the 19th century, a liberal theological line of thought emerged out of Germany, popularized by the scholar Friedrich Schleirmacher. It essentially stripped the miraculous out of the Bible by downplaying the Scriptures as being divinely inspired, reducing the Bible to a collection of human documents. This theology began to be adopted by more and more scholars of the day, and it began to influence many within Protestantism.

In response to this, a series of pamphlets was produced from 1910–1915 that argued for the “fundamentals” of the Christian faith. Initially there were five core theological positions identified: the inerrancy of Scripture, the virgin birth, the historical legitimacy of Jesus’ miracles, Jesus’ bodily resurrection, and the substitutionary atonement of Jesus. In later booklets, the deity of Christ and his second coming were added, making at least seven historical distinctives that the early fundamentalists deemed essential Christian beliefs.

Alignment with the creeds

Now, when I look at how fundamentalists were initially defined, it does not look or sound so scary and unreasonable. I do not think it is too far a stretch to say that most EMC constituents would agree with these things (or at least six of the seven).

In fact, a cursory look at church history shows that most of these defining points of the initial fundamentalists are found within the two major church creeds. These creeds, of course, are the Nicene Creed and the Apostles Creed. While I understand the EMC is not inherently creedal, Christian history put a lot of emphasis on these two, and Reformers like Luther and Calvin emphasized their importance to the Christian.

When I look at how fundamentalists were initially defined, it does not look or sound so scary and unreasonable. I do not think it is too far a stretch to say that most EMC constituents would agree with these things (or at least six of the seven).

Both creeds explicitly affirm the virgin birth, resurrection, deity, and second coming of Christ, with the legitimacy of Jesus’ miracles being inferred (due to his resurrection). That means that five of the seven “fundamentals” of historic fundamentalism are rather clearly stated in the two most important creeds the church has produced.

That leaves us with the two other points of historic fundamentalism to consider: the inerrancy of Scripture and the substitutionary atonement of Christ. With regard to inerrancy, it is abundantly clear that the early church believed in the Scriptures as being free from error.

Inerrancy of Scripture

(iStockphoto.com)

Clement of Rome, writing at around AD 100, wrote that the Scriptures were the “true utterances of the Holy Spirit” that were free from any “unjust or counterfeit character… written in them” (“The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians,” The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus). Irenaeus of Lyons wrote that “the Scriptures are indeed perfect, since they were spoken by the Word of God and His Spirit” (“Against Heresies,” The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus). Many other writings from the early church support this sentiment, including those of Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, Jerome, and particularly Augustine of Hippo.

Suffice it to say, the idea that the Scriptures were divinely inspired and thus free from error is an idea grounded in the Scriptures themselves (2 Timothy 3:16, 2 Peter 1:21, Psalm 12:6) and defended vigorously throughout church history. I have no reason to believe differently!

Christ’s substitutionary atonement

The substitutionary atonement of Christ is the most contentious and likely to be rejected of the seven. To most fundamentalists—particularly those of a Reformed persuasion—this is of paramount importance. David Martyn Lloyd-Jones once commented that he thought it impossible to fellowship with those who would deny this doctrine. J. I. Packer and Al Mohler have both said that a rejection of the penal substitution atonement (PSA) theory is a rejection of the gospel itself. Many others have made similar statements, staunchly linking PSA to the heart of the gospel.

While there are other atonement theories, I’d venture to guess that the nearly unanimous view within fundamentalist circles is penal substitution. Personally, I think the atonement is more complex than any one theory could account for, but I would also say there are some substitutionary elements within it.

Why I don’t call myself a fundamentalist

If you have been keeping track, you can probably see I would check off six and a half of the seven central points of historic fundamentalism, with my only real quibble being the insistence on penal substitution as the only valid atonement theory. Does this make me a fundamentalist? Historically speaking, I would guess it would! Yet (if you recall from earlier in the article), I stated that I have distanced myself from adopting the title of fundamentalist. So, what gives?

Well, as I said before, today’s definition of a fundamentalist differs from that of the early 20th century. If someone labels me a fundamentalist today, I doubt they mean that I am someone who adheres to these seven doctrinal points. More than likely, they are attempting to paint me as an anti-intellectual, an isolationist, or an intolerant Pharisee who lacks the love and mercy that Jesus exemplified. I am not sure about you, but I do not want to be associated with that!

If someone labels me a fundamentalist today, I doubt they mean that I am someone who adheres to these seven doctrinal points.

A good friend of mine recently told me that modern-day fundamentalism seems to be an attitude of extreme exclusion, meaning they draw a line in the sand and anyone who does not conform to their rigid ideas is dismissed outright (or condemned to hell). I agree with my friend; this attitude is a major reason why I can’t see myself as a fundamentalist today.

Still, there are things to appreciate

However, that does not mean I cannot find things that I appreciate within modern fundamentalist circles. For instance, many of the fundamentalists that I know are deeply in love with the Scriptures. Not only are they consistently reading and studying the Bible, but many of them also excel at memorization. The ability to recall where and what a particular passage someone might be talking about is very valuable when you are sharing or teaching about your faith. I have even heard members of other branches of Christianity laud the fundamentalist’s love of the Bible, with a wish that same zeal would be found in their own tradition.

(Lightstock.com)

The ability to recall where and what a particular passage someone might be talking about is very valuable when you are sharing or teaching about your faith.

Something else I admire about the fundamentalists is their desire to educate their children. I know that this is not a trait that some will find positive, but we made the choice to homeschool our children three years ago. As my wife began sifting through possible curriculums, I came to realize there are far more than I thought! And many of the options come from the conservative evangelical/fundamentalist camp. While we may not agree with all the areas of emphasis and practice within some of these curriculums, it shows a genuine concern to raise up the next generation with a robust understanding of the Christian faith.

Many of the small Bible colleges that exist within North America were started by groups that fit the fundamentalist definition, and they produced hundreds of faithful missionaries and pastors over the years. For these kinds of things, I am truly thankful.

A source of hurt and blessing

Ultimately, an exact definition of fundamentalism can be difficult to nail down. Because it is so often used in a derogatory sense, there can be a sense of shame attached to it. And we must be honest with ourselves: there are plenty of fundamentalists who have done reprehensible things and thus damaged the body of Christ. No doubt there are some readers who have experienced these unfortunate things for themselves, as I have. I have been hurt by the attitude and actions of a few people in the church who fit many of these negative stereotypes.

However, I have also been tremendously blessed and encouraged by people on the fundamentalist side of the spectrum. I certainly would not be who I am today if I had not gone to Sunday school with Mrs. Brad, whose strong emphasis on sword drills and memorization helped instill a love of Scripture in me. I would not be who I am today if it wasn’t for the Bible college I went to, which was certainly grounded in fundamentalist ideals.

I would not be who I am today without the living example of Mr. Ens, whose entire life was in service of King Jesus, and whose walk matched his talk. I know of no one who could speak ill of the man, whether they agreed with him on all points of doctrine or not. His boldness in sharing the gospel, knowledge of the Bible, and his incredible prayer life were inspirational to a young and anxious me.

So, while I may not link myself to today’s fundamentalism, I can confidently say that I would not be who I am now without the faithful fundamentalists who helped give me a foundation and love for my faith.

Other articles in this series:

Why this young theologian was drawn to Reformed evangelicalism

Ancient, continuous, and meaningful: why traditional, liturgical church practices draw me

Personal, hope-filled and Spirit-empowered: the appeal of charismatic evangelicalism

Compassionate, questioning and messy: the appeal of progressive Christianity